Case Study: Energy Exploration Mission to Afghanistan, 1999

Location: Kabul, Mazar-i-Sharif, Sheberghan, and Kandahar, Afghanistan

Date: May 1999

Client Context: Early-stage assessment of Afghanistan’s post-war power infrastructure

Background

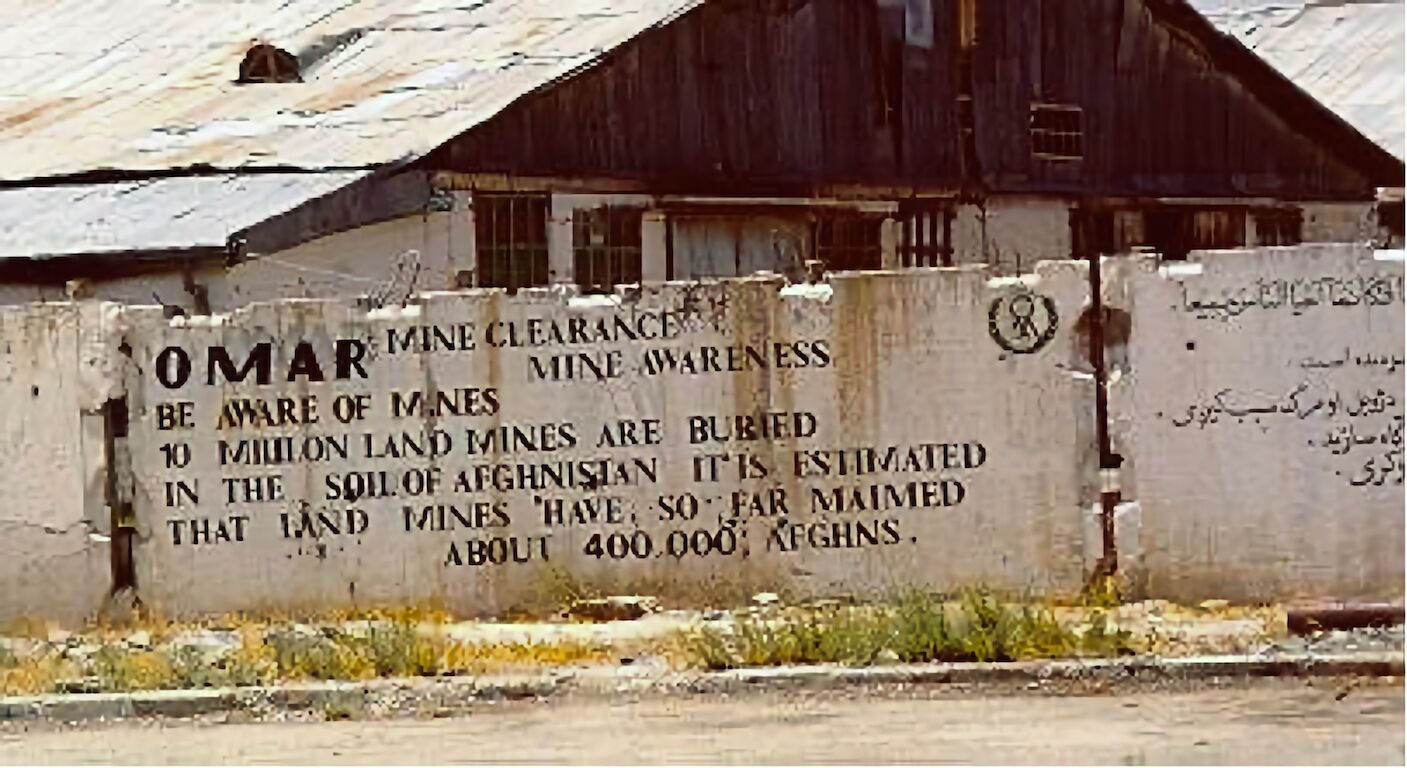

In 1999, Afghanistan stood at the crossroads of recovery and realignment. After years of brutal conflict, the Taliban had consolidated control over most of the country, filling the vacuum left by the Soviet withdrawal and subsequent civil war. The United States and United Kingdom maintained diplomatic channels with the Taliban leadership at this time, hoping to stabilise the region and curb opium trafficking, though the regime remained internationally controversial and largely unrecognised. Foreign visitors were exceedingly rare, and the notion of commercial engagement was practically unheard of.

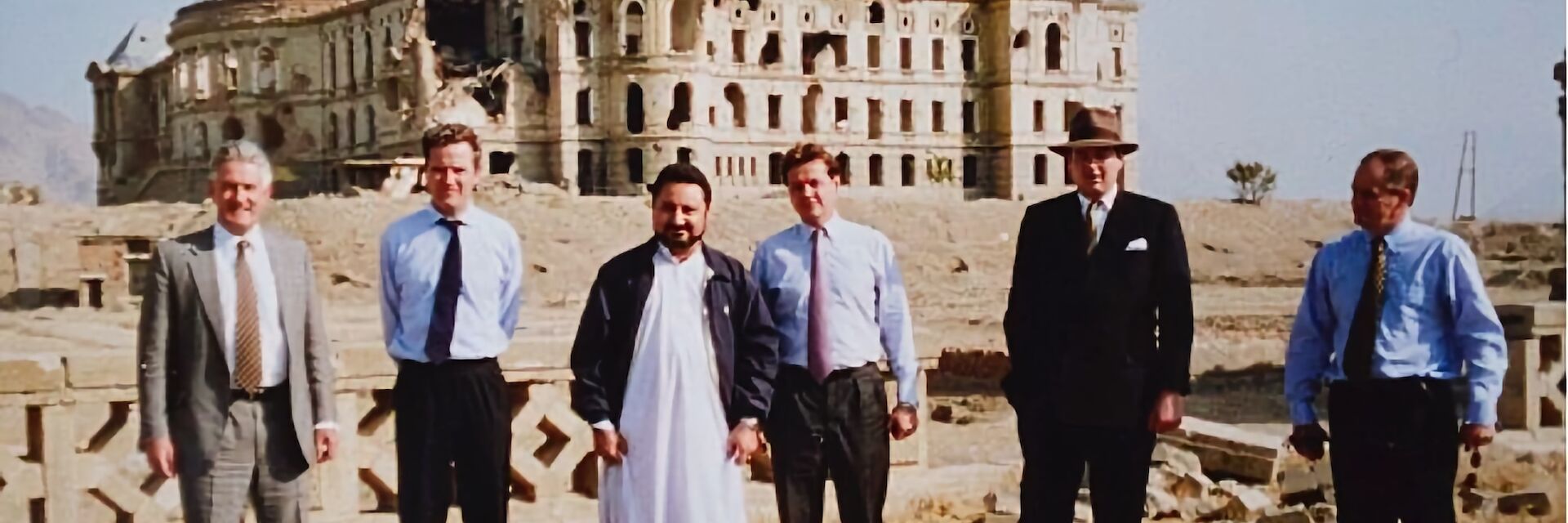

It was against this backdrop that CESS’s Founding Director, Mike Craigie, embarked on a unique mission to explore the feasibility of deploying gas turbine technology in Afghanistan. Travelling alongside Stuart Bentham (a Sandhurst-trained former military officer) and Lord Michael Cecil, a member of the British aristocracy with longstanding business and diplomatic interests in the region, the delegation was hosted by Afghan-American telecom entrepreneur Mr Ehsan Bayat.

The following has been provided by CESS Founder Mike Craigie’s journal on his visit to Afghanistan in 1999.

Kabul

We left Heathrow on Derby Day, 1999, and flew to Dubai, where we caught an evening Ariana Afghan Airlines flight to Kabul. When we landed, we were received as guests of the Taliban, under the protection of our host, Ehsan Bayat. We stayed in his company’s villa in the city.

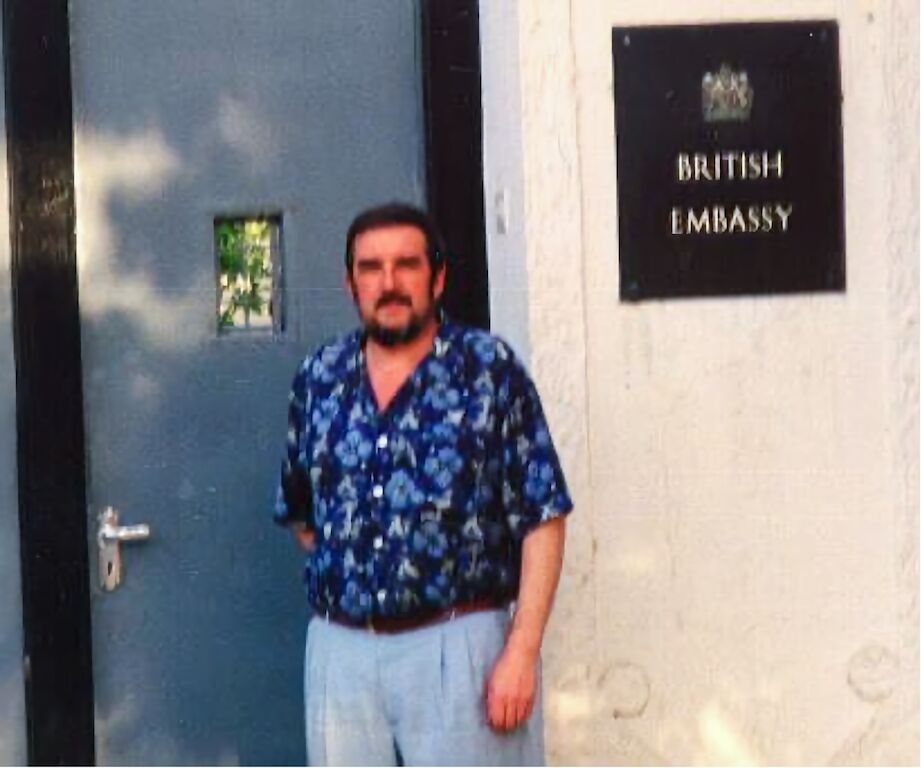

Driving through Kabul, the remnants of war were everywhere; burnt-out tanks, armoured vehicles, and debris left by years of fighting. We visited the British Embassy, but the gate was locked, and there wasn’t a soul in sight. That told me everything I needed to know about how isolated this place had become.

Northern Excursion: Mazar-i-Sharif to Sheberghan

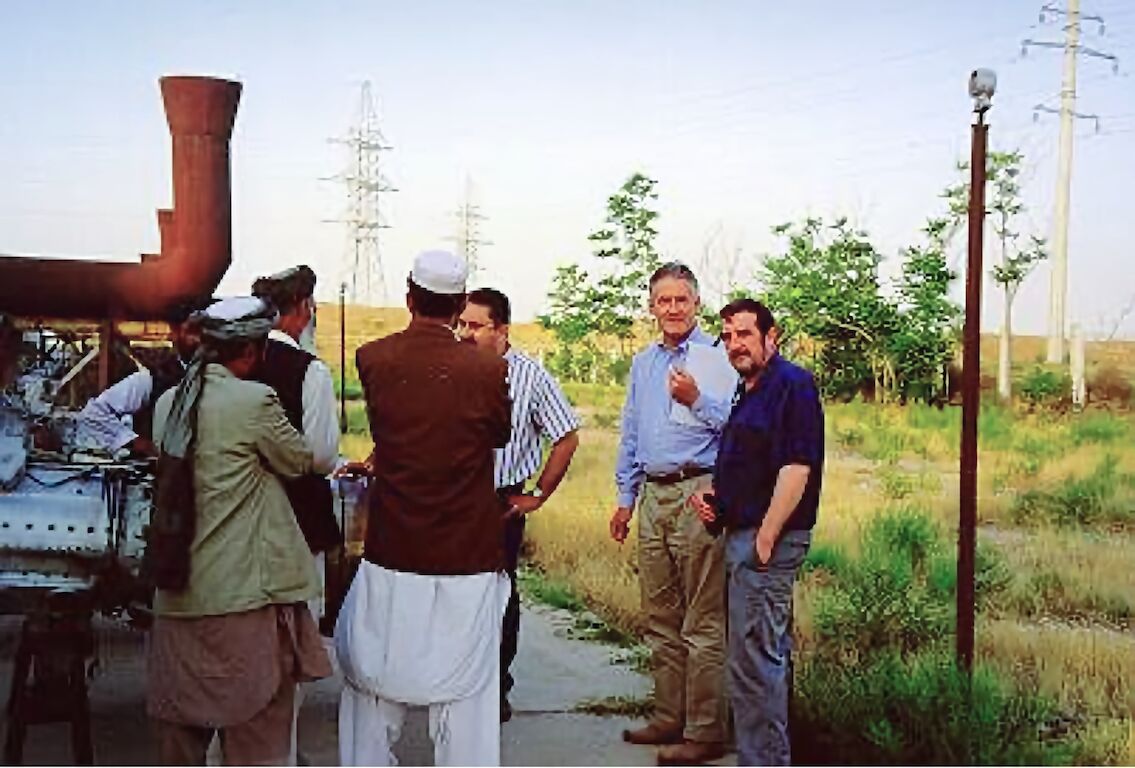

On our second day, we flew to Mazar-i-Sharif for a regional tour. It had once been the stronghold of the Northern Alliance and had seen its share of violence. That evening, despite a nationwide Taliban curfew, Ehsan decided we’d drive to the Sheberghan oil fields. No one questioned it. We just got in the car and went.

The roads were quiet but not empty. We passed convoys of lorries and buses — not transporting passengers, but poppies. Each vehicle had a few armed men guarding the cargo. The atmosphere was tense, even inside our vehicle.

When we reached a checkpoint near Sheberghan, things escalated. Searchlights lit us up and men started shouting. A group of heavily armed fighters surrounded us, all carrying large automatic rifles and clearly on edge. I asked what the issue was. One of our escorts, sitting right beside Taliban guards in the back seat, quietly explained that our team from Kabul didn’t know the password for this region. Not ideal.

There was a lot of back-and-forth, raised voices, and weapons in view, but eventually, they let us through. We arrived at the guesthouse in one piece, though I wouldn’t say we were relaxed.

That night, after dinner, Ehsan stepped into the walled garden with what he called his new ‘mobile phone’. It had a huge dish-shaped antenna, so calling it “mobile” was generous, but it worked.

He seemed to be in intense conversation with someone and waved me over, passing me the phone. A well-spoken woman asked how I was finding Afghanistan. I spoke freely, not aware of the audience beyond the garden walls:

“I’d been most terrified at the idea of coming to Kabul, 99.9% of the world is avoiding it, however, since I arrived I have been spectacularly impressed by the people, the hospitality, and the scenery. The potential for installing gas turbines and reconnecting the grid has made the trip worthwhile. I even hope to return.”

Kandahar

Our flight home from Kabul was unexpectedly diverted to Kandahar. The main departure terminal had been converted into the spacious new Taliban headquarters. Inside, the floors were lined with huge cushions and the room was crowded with guards holding automatic weapons.

I was led forward and introduced to the Taliban Supreme Leader, Mullah Omar. He had lost an eye during the war with the Soviets and was rarely seen in public. He sat at the centre of the room, surrounded by armed men. No one spoke unless spoken to.

Ehsan introduced me, “This is Mr Mike Craigie, who has been looking at our power situation.”

There was a pause. Mullah Omar’s translator smiled and said, “Yes, we heard Mr Mike on Voice of America Radio last night.”

Only then did I realise the satellite call had been a live interview broadcast on the radio - and that the Taliban leadership had been listening in.

Outcome and Legacy

Mike’s visit represented one of the first Western technical assessments of Afghanistan’s power infrastructure after the civil war. Despite significant political instability and personal risk, the mission successfully identified potential grid connection points and verified that key infrastructure remained intact for future turbine deployment.

This extraordinary journey underscores CESS’s readiness to engage even in the most challenging environments, combining technical curiosity, geopolitical awareness, and the good sense to choose a diplomatic tone when you don’t know who’s listening.